A NOT SERIOUS GUEST WRITER — HENRY OLIVER

Henry Oliver is a freelance writer and editor. He was previously The Spinoff's music editor, the editor of Metro, a bar owner, intellectual property lawyer, and bass player*

I first met Henry, and his wife Amber on Karangahape Road. It was when Coco’s Cantina was hardout breaking rules, winning hearts and carving a path to make people see the cultural magic of ‘red light’ road.

Well, there was another little joint, just along a bit, where the beverage offering was bloody refreshing and I’m not just talking thirst quenching. A place where the scent of quiet but exciting rebellion matched the bouquet of the standout bevvies on offer. That bar was D.O.C. and it was Henry and Amber’s.

I was working as a wine sales rep at the time and found their place to be a delightfully disarming gaff. While venues downtown were getting a multi-million dollar makeovers, thanks to the proceeds of gambling, their place was the exemplar of casual, welcoming, come-as-you-are, make-yourself-at-home seriously inclusive sort of wine bar that utilised a space rather than tried to reinvent it. And that, my not serious, wine curious cronies, was right up my strasse. And then it closed.

Henry writes a line or two of why and how his foray into hospo started and finished.

Please enjoy this personal piece by the most personable, sometimes serious but for now, totally not serious, Henry Oliver.

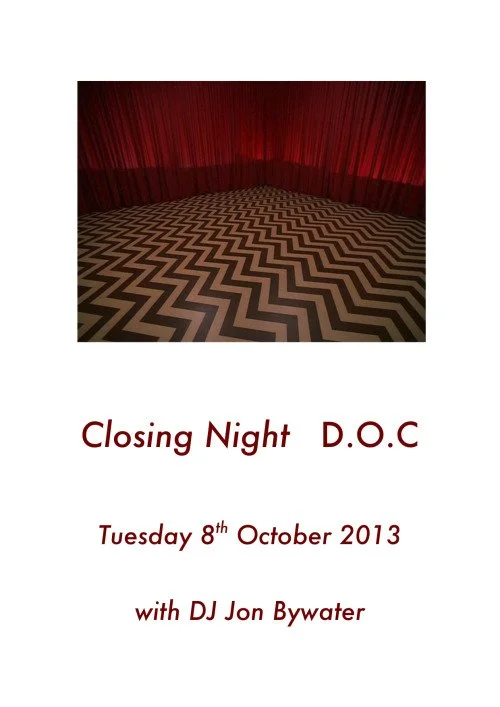

D.O.C. — Henry Oliver’s bar on K Road, Tāmaki Makaurau

The Peril of Being Early

In late 2006, my now-wife Amber and I moved back to Auckland to get married, expecting it to be a pitstop. We’d been living in Brooklyn where our social life revolved around dive bars with $1 PBRs, or unpretentious wine bars where, for the price of three 2025 coffees, you could get a decent glass of wine alongside a cheese board or happy-hour steak frites.

Our plan was simple: tie the knot, see friends, sort visas, and return to New York. Life, of course, had other plans. Visas were complicated, a summer touring the length of New Zealand was rather enticing, and suddenly we were staying. Soon, I found myself working at The Village Winery in Mount Eden and enrolling in law school. But as we settled into our new life in our mid-twenties, we faced a persistent, mid-twenties problem: we had nowhere to drink. The established wine bars felt out of reach, and the dive bars were more venues than social hubs. There was an obvious gap where a relaxed, grown-up-but-not-stuffy, wine-friendly bar should be. The solution, born more of naivety than expertise, was inevitable: we’d open it ourselves.

The sum total of my hospitality experience was the wine store and a single night serving beers at a gallery opening in New York. Amber had waited tables at a vegan diner there for a while too, but neither of us really knew what we were getting into. Our business plan was arithmetic of simplicity: buy beer for $1.70, sell it for $6. The volume, we assumed, would cover everything else. That year at the Village Winery had been a crash course in the cheaper end of the market—the hidden gems, the reliable recommendations. I wanted to translate that into a bar list: good wine, cheap.

We opened D.O.C. (which stood for Department of Conversation, not Denominazione di Origine Controllata) in February 2008. Our opening list: Kumeu Village Chardonnay, Te Mata Woodthorpe Sauvignon Blanc, Rocca delle Macie Vernaiolo Chianti. House wines at $7 a glass, “Premium” at a daring $8. We had Quartz Reef Méthode Traditionnelle for $40 a bottle and a couple of Laurent-Perrier Brut at $110, waiting for gallerists who’d had a successful opening.

I was stubborn in offering Te Mata Awatea for a mere $10 a glass for the first few weeks. It didn’t move. We shifted it to bottle-only ($45), then dropped it entirely.

The market’s message was brutally clear. People didn’t want “nice” wine from us. They wanted wine that was cheap, and preferably either ice cold or French. My dream of expanding to eight or ten wines, of introducing a Cru Beaujolais or a dry Riesling, evaporated. I’d hoped to share wines I loved, not just those that were good value. Instead, we adapted. We found that selling bottles at a sharp $30 encouraged sharing, which fostered the exact social vibe we wanted — and was, frankly, less work. The community that formed was everything we’d hoped for: a vibrant, cross-pollinating mix of fixed-gear bike riders, architects, ad men, hairdressers, art school kids, and Tuesday night regulars with church-goer dedication.

For three years, it was a blast, but the financial logic was frail. Our $8 premium glass was a hard sell in a culture that drank wine but wasn’t that interested in it. We were trying to sell to a customer that didn’t yet exist. The second three years, as we started other careers and tried to manage from a distance, were a grind of diminishing returns. We closed in 2013, left with an IRD debt that took years to clear and a space I couldn’t bear to revisit for a long time.

A few years later, as editor of Metro, I re-engaged with Auckland’s hospitality scene and witnessed a revolution. Natural wine — with its funk, its cloudiness, its biodynamics and hand-drawn labels — had recalibrated a generation’s expectations. Places like Bar Celeste and Clay were at the vanguard. They weren't just selling wine; they were selling a story, an ethos, an identity. They served challenging, skin-contact orange wines and pet-nats to young people who weren’t just willing to take a chance, but were eager to. The most startling revelation? The prices. Where we had struggled to justify $8, they were effortlessly charging $15, $18, even $22 for a glass. The audience wasn’t buying a drink; they were buying authenticity, agricultural integrity, and membership to a club.

Looking back, my attempts at wine service at D.O.C. weren’t a failure of concept, but a casualty of timing. We were solving a problem—the lack of a relaxed, unpretentious space for our generation—with a solution that was half a decade too early. The revolution that followed wasn't just about different wine; it was a shift in language, aesthetics, and consumer psychology. Natural wine arrived not as a “premium” category, but as a counter-cultural one. Its higher prices were framed not as a luxury, but as the justified cost for ethical production and therefore consumption. The market had been primed by the rise of craft beer, specialty coffee, and artisanal food — a culture now defined by provenance and narrative.

Our mistake was trying to sell quality in an era that wasn’t yet asking for it. We offered a well-made Chianti; they later offered a connection to a Tuscan vineyard. Our $8 pour was a transaction. Their $15 glass was an experience. The bitter irony is that the very community we provided a space for became the core demographic for this new wave.

But now that wave seems to be cresting. Wine consumption is down at most local restaurants. Not only are wines more expensive (the multiplier restaurants use to price their wines compared to retail appears to me to be out of control, but that’s a subject for another time), customers tend to stick to one or two glasses each rather than the bottles we used to see shared across our tables. The ‘experience’ of the $22 glass has finally hit the ceiling of the cost-of-living crisis. We have moved from the era of “cheap and cheerful,” through the era of “expensive and expressive,” and arrived at a point of "prohibitive and precious."

The irony of the current moment is that Auckland might need something like what D.O.C. offered in 2008: a place where the barrier to entry isn’t $20+. As the natural wine hype settles into a permanent fixture as another regular wine category, the pretension that often accompanied it — the need for a dissertation with every pour — is starting to grate. What would the $7 glass of pretty good wine look like in 2026? $10? $12? Is it even possible to have a sustainable business with glasses under $15? If someone’s already pouring it, let me know!

— by Henry Oliver

Follow Henry on Instagram

*I couldn’t let you go without sharing some bonus ear candy from our guest writer >

Shyness Will Get You Nowhere, by Die! Die! Die!

Written by — Andrew Wilson, Henry Oliver, Michael Prain

we’re super grateful to our pals at antipodes water company. they supply us with the good water for our chats. antipodes is an artesian water that contains no chemicals, and when you’re pouring an organic wine that is gold. the mineral content also keeps the palate fresh so you can taste the wine the way the winemaker and nature intended you to. thanks antipodes, you’re the bomb. antipodes.co.nz